By Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D.

Director, Institute for Traditional Medicine (Portland, Oregon)

BACKGROUND

For years, Western practitioners of Chinese medicine and virtually all proponents of natural health care have tried to convince people that they should stop drinking coffee, as an important step towards becoming healthier. Coffee was blamed for contributing toxicity to the body and to “burning out” the adrenal glands, and was more generally disdained as being one of many mass market components of an unhealthy food chain. Few opponents of coffee considered it a natural herb with a history of medicinal use; instead, focus was on medical reports of adverse effects of caffeine and general impressions that stimulating beverages had to be unhealthy. As it turned out, most reports of significant adverse effects from consuming coffee or from ingestion of caffeine were incorrect, due to poor study methodology, though this does not contradict the clear potential for adverse effects from high levels of caffeine or other components of coffee. In recent years, drinking green tea, a beverage that had also been rejected by coffee opponents due to worries about its caffeine content, has been shown to be one of the healthiest of habits. The antioxidant activity of the green tea phenols (catechins) has been a major focus of attention; coffee also contains antioxidant phenols. Tea and coffee are traditional beverages with a long history of being enjoyed by billions of people. Therefore, they ought to be re-examined. Few foods or beverages are perfect for everyone, but coffee might be entirely acceptable for many people, who will do fine without being warned to stop enjoying their beverage of choice, so long as it is enjoyed in moderation. This article examines coffee from ancient and modern perspectives, with a view towards interpretation through the lens of Chinese traditional medicine, a field that has been employed to analyze virtually everything that people consume.

COFFEE HISTORY

Coffee refers to the beans (seeds) harvested from plants of the genus Coffea of the family Rubiaceae and to the beverage brewed from it. Botanical evidence indicates that Coffea arabica, the first coffee to be widely used as a beverage, originated on the plateaus of central Ethiopia, several thousand feet above sea level. According to the Kaldi coffee legend, the potential for consuming coffee was first discovered when a goat-herder in Abyssinia, while groggily basking in the sun, observed his goats dancing on their hind legs after eating some of the red berries. He tasted the berries and his sleepy eyes opened. He took some to the village and the people there also liked it, especially the monks, as it kept them awake during their prayers. This story is somewhat like the one told for epimedium, known in China as “horny goat weed.” It is said that a goat herder noticed that his herd became very sexually active after grazing in a field of this herb. He then tried a tea made from the herb, with satisfactory results.

Coffee beans on the vine

Chinese treasure ships sailed in search of medicinal herbs from distant lands which were then brought back to China for incorporation into the rapidly increasing Materia Medica. However, they were unable to acquire coffee, which was intensively regulated by the Arabians. Eventually, some beans were taken to India by a Moslem pilgrim who smuggled out the fertile berries and it was cultivated there in the 17th Century. Coffee is described in the Indian Materia Medica of 1908 (1): “Coffea arabica and several other species of the plant are luxuriantly cultivated in Southern India, Madras, Mysore, Coorg, Travancore, and Cochin.” Its actions and uses, described in this text are listed thus:

Actions: Cerebro-spinal, respiratory, gastric, and renal stimulant; antisoporific, efficient diuretic and antilithic; assists assimilation and digestion, promotes intestinal peristalsis, lessens tissue waste, and decreases the excretion of urea. It reduces the amount of blood circulating in the brain and brings it to the nervous tissues under pressure. It allays the sense of prolonged mental fatigue and keeps off sleep for some time. It increases reflex action and mental activity.

Uses: Coffee is a palliative in spasmodic asthma, in whooping cough, delirium tremens, hysterical affections, and in the palpitation of the heart; it is recommended in infant cholera; successful in chronic diarrhea. Coffee and caffeine have been used as a diuretic in dropsy….A strong cup of coffee is considered a good protection from the effects of malaria. In their raw state, coffee berries are prescribed for hemicrania and intermittent fevers. It is well known that moderate quantity of coffee is not only not harmful, but is even beneficial.

Today, about 80 percent of India’s coffee is grown in the southern state of Karnataka, and is often sold as Mysore coffee, after the former name of that state. Dutch traders also brought coffee further east, to Java and Sumatra, which became famous coffee sources. Southeast Asia was on its way to being a major world source of coffee in the mid-19th century when a plant disease wiped out many of the crops, turning the world’s attention to coffee from Brazil and other areas. But, the coffee plantations eventually recovered. By 1887, coffee had made its way to Tonkin, in what is now Vietnam, and from there it arrived in China, thanks to a French missionary who planted some coffee beans in Yunnan. The Chinese initially showed little interest in this drink favored by Westerners (except in places like the Western-influenced city of Shanghai), but a hundred years after its first introduction to China, China has become a major producer and an exporter of beans (green, roasted, or finished products) and coffee is offered in all major cities of China (see Appendix).

COFFEE IN CHINESE MEDICINE: A HEALTH BEVERAGE

The Rubiaceae family of plants, to which Coffea belongs, is a traditional source of several Chinese medicinal herbs, including gardenia fruit (zhizi), oldenlandia (also called hedyotis; baihuasheshecao), morinda (bajitian), rubia (qiancaogen), and uncaria (gouteng). Each of these has been characterized in the Chinese system as to nature, taste, and therapeutic actions; coffee has been analyzed as a medicinal herb in the same way. It should be kept in mind that, when used as health products, herbs are given in a certain dosage range to get the desired effects. Herbs in the form of seeds and beans are typically given in dosages of 6-18 grams in one day. Though everyone has their favorite preparation, a cup of coffee is typically made from 6-9 grams of the ground beans. So, 1-3 cups of coffee is about the correct range. Many Westerners consume more (and use mugs that contain 2 or 3 cups each), so the effects in those cases, which could include some adverse effects, are not necessarily the beneficial ones typically encountered in the dosage range under consideration here.

In the Chinese medical-dietary system, the green bean of coffee would be classified as an herb that regulates liver qi, which is its therapeutic route to strong energy stimulation (attributed chemically to caffeine’s action on the nervous system). The green bean is of the color of the wood element (associated with liver); more important to classification, however, is the concept that when the liver qi is constrained, the entire body energy becomes depressed. By vigorously dredging the stagnated liver qi, a strong sense of mental and physical vitality is experienced. The early use of coffee beans to regulate menstruation is consistent with the Chinese medical approach of regulating menstruation by dredging stagnant liver qi. The green coffee bean also cools the constrained liver qi. When the bean is roasted, it retains its basic medicinal properties, but transforms from a cooling herb to a warming herb. Roasting herbs is a common processing method used in China.

Coffee not only regulates the liver qi, but also purges the gallbladder. In fact, modern research in Chinese medicine suggests that most herbs that regulate liver qi have this effect on the gallbladder as an integral part of the qi-dispersing action, but some herbs have greater gallbladder purging effects than others. The liver (and gallbladder) regulating properties of coffee explain its ability to protect against formation of gallstones and its ability to alleviate constipation. This action has been attributed to chlorogenic acid and other constituents found in coffee.

When liver qi is dredged, its natural tendency is to flow upward; when the gallbladder is purged, its natural tendency is to move downward. Thus, consumption of coffee has a blended upward and downward action. Healthy individuals will experience this as a balanced action, but individuals with certain health problems may experience either an excessive upward or excessive downward reaction.

The bright red berry that encases the coffee bean signifies this herb as a treatment for the heart. Coffee has the effect of opening the orifices, it thus has the action of stimulating and focusing mental activity, something like the effect attributed to the medicinal herb acorus (shichangpu). The bitter taste of the coffee bean signifies its detoxicant qualities. Its effects are comparable to that of dandelion (pugongying), which disperses accumulations by purging the gallbladder and promotes urination (as do caffeine-containing beverages).

The coffee taste, although obviously bitter, is also partly sweet. We know this because addition of a small amount of sugar or other sweetener quickly makes the beverage sweet tasting, which does not occur with strictly bitter-tasting herbs. The sweet taste is associated in Chinese medicine with a tonic effect, particularly for the spleen. As mentioned in the Indian Materia Medica, coffee “assists assimilation and digestion.” Thus, coffee can help ameliorate liver-spleen disharmony associated with liver qi stagnation and spleen weakness. On the other hand, its liver dredging effect is strong and its tonic effect is weak, so a person with severe liver qi stagnation and weakness of the spleen may have the adverse experience of released liver qi impinging on the weakly resistant spleen/stomach system, causing gastro-intestinal distress.

In sum, coffee dredges the liver to regulate the flow of liver qi, purges the gallbladder, opens the heart orifices, warms the blood circulation, detoxifies, and gently tonifies. However, while coffee dredges the liver qi, it does not necessarily smooth or soothe the liver qi. Therefore, one has to be cautious about the amount consumed and certain individuals will find the otherwise desirable effects distressing: releasing stagnated qi but not regulating its flow. As with other Chinese herbs, coffee would best be used in combination with herbs to moderate and enhance its effects. As an example, peony root (baishao) is often used to “soften” the liver, and smooth the flow of qi. Because coffee is consumed as a flavorful beverage, to pursue such an approach would best be done by having additional herbs taken in a form that wouldn’t alter the taste of the coffee, such as in pills. Excessive amounts of coffee will agitate the liver yang and even stimulate internal wind. Prolonged use of excessive amounts could thereby damage the blood, but for moderate amounts it serves as a valuable therapy for stagnated liver qi, with constricted circulation of blood, and constrained gallbladder function, with constricted elimination of damp and heat.

The herb in the Chinese medical system that is most similar to coffee in its overall actions is bupleurum (chaihu). This herb also strongly dredges the liver qi, and by itself does not smooth the qi, so it also has the potential for adverse reactions if used excessively or if it is not formulated properly for the individual who uses it. The greatest problem with use of bupleurum is when liver blood and yin are deficient, in which case the dredging action and stimulation of qi circulation is too strong to yield a desired reaction. This potential reaction to bupleurum is usually ameliorated by using sufficient quantities of tang-kuei (danggui) and peony along with it. Bupleurum only mildly purges the gallbladder but is often combined with chih-shih (zhishi) to increase this purgative action, which helps to balance its upward qi flow with the downward bile flow. Bupleurum formulations can act as stimulants to the mental activity yet are calming for those suffering from anxiety and oppressive conditions, so they are often known as an anti-depression therapy. For coffee drinkers, it is found to be both mentally stimulating and calming.

The herb in the Chinese medical system that is most similar to coffee in its overall actions is bupleurum (chaihu). This herb also strongly dredges the liver qi, and by itself does not smooth the qi, so it also has the potential for adverse reactions if used excessively or if it is not formulated properly for the individual who uses it. The greatest problem with use of bupleurum is when liver blood and yin are deficient, in which case the dredging action and stimulation of qi circulation is too strong to yield a desired reaction. This potential reaction to bupleurum is usually ameliorated by using sufficient quantities of tang-kuei (danggui) and peony along with it. Bupleurum only mildly purges the gallbladder but is often combined with chih-shih (zhishi) to increase this purgative action, which helps to balance its upward qi flow with the downward bile flow. Bupleurum formulations can act as stimulants to the mental activity yet are calming for those suffering from anxiety and oppressive conditions, so they are often known as an anti-depression therapy. For coffee drinkers, it is found to be both mentally stimulating and calming.

PROPER ADVICE

As with all herbs and foods, the role of the trained Chinese medicine practitioner is to give advice based on the principles of herb therapeutics developed over the centuries and modified by modern knowledge. In the case of coffee, as with most herbs, emphasis should be on how well the herb matches the needs of the individual and what other herbs might be used to make the key herb function better. Since many people drink coffee in quantity, it is as though they already have a key herb of a formula, and it may or may not be suited to them. While an herb may not be appropriate for some individuals, one should not simply advise all people to avoid this herb, just as one would not advise everyone to avoid bupleurum. A typical negative attitude towards coffee is summed up by acupuncturist Brian Carter, who described his encounter with and participation in the field of Chinese medicine for his journal the Pulse of Oriental Medicine:

At one point in my training, I went back to smoking cigarettes. It was a guilt-laden 6 weeks! It seemed hypocritical to want to be a healer while destroying my health. And I felt like I had to hide it. I quit to be a better example to my patients, and not to have to hide anything. I also had to quit coffee. I knew from Chinese medicine that it wasn’t helping me with my impatience and irritability. It was worsening my liver qi stagnation! I had to give it up and take herbs instead. I had to practice what I preach.

While he is correct that his own syndrome-one of impatience and irritability-may have been worsened by drinking coffee, he was already preaching to others that they too should stop drinking coffee, not recognizing that coffee is an herb, just like the ones he intended to use instead of it. And, nowhere in the Chinese medical system is it pronounced that coffee worsens liver qi stagnation (in this article, I have suggested that it does just the opposite, consistent with both its energizing effects and cholagogue action). It is always appropriate to point out the correct dosage range for coffee and suggest alternative beverages, such as green tea, for those who currently consume too much coffee, to divide their beverage consumption.

For a number of years, proponents of natural health care rejected virtually all foods and beverages that were commonly consumed, complaining that they were unhealthy. This led to recommendations to avoid those foods, sending people in search of alternative health foods. Gradually, research has proven that people who consume appropriate amounts of the substances rejected under such advice avoid diseases rather than bring them on. While some of this reaction to items belonging to the common food supply was based on philosophical ideas that arise during the 19th century, there was apparent support from modern science.

When large-scale population studies were first conducted in the U.S. and Europe, beginning in the 1950s, there was a reported association of coffee consumption with cardiovascular diseases: the more coffee consumed, the worse the health problems. However, as sophistication in conducting these studies and analyzing the results developed over the years, it was found that people who drank large amounts of coffee were often the same people who smoked large amounts of cigarettes, and consumed high calorie diets, with low amounts of fruits and vegetables. As these other factors were isolated by improved statistical analysis, it turned out that coffee was only a contributing cause at high dosage; at moderate levels, it turned out that coffee has been a factor in attaining better cardiovascular health (3). In a similar manner, caffeine was thought to be a cause of significant health problems, but virtually all of these concerns also evaporated for reasonable intake levels when studies were improved. Consumed in moderation, caffeine-containing natural beverages, such as coffee and tea, offer numerous health advantages. Coffee began as a medicinal herb, and remains one. The fact that it is enjoyed in beverage form by billions around the globe does not detract from its health values: not everything healthy is inconvenient and rare.

Although the benefits of coffee-as revealed in some recent studies-can be exaggerated, there is clear evidence that, even beyond cardiovascular considerations, coffee drinking in moderate amounts has a positive effect on health, just as was said in the Indian Materia Medica. In one recent review of the situation, an enthusiastic writer, Kenneth Davids, portrayed the situation this way (4):

Coffee has been a medical whipping boy for so long that it may come as a surprise that recent research suggests that drinking moderate amounts of coffee (two to four cups per day) provides a wide range of health benefits. Most of these benefits have been identified through statistical studies that track a large group of subjects over the course of years and match incidence of various diseases with individual habits, like drinking coffee, meanwhile controlling for other variables that may influence that relationship. According to a spate of such recent studies moderate coffee drinking may lower the risk of colon cancer by about 25%, gallstones by 45%, cirrhosis of the liver by 80%, and Parkinson’s disease by 50% to as much as 80%. Other benefits include 25% reduction in onset of attacks among asthma sufferers and, at least among a large group of female nurses tracked over many years, fewer suicides. In addition, some studies have indicated that coffee contains four times the amount of cancer-fighting antioxidants as green tea.

As pointed out in the description of coffee action as viewed through the system of traditional Chinese medicine, coffee offers benefits, but is not for everyone. Some people are very sensitive to caffeine effects, usually as the result of liver qi disorders that are worsened when the circulation of qi is stimulated (e.g., persistent blood deficiency with weak spleen qi or upward flow of stomach qi). Some are sensitive to other ingredients in coffee, and will react even to decaffeinated versions. However, for the majority of people, as experience shows, coffee is enjoyed both for the experience of drinking it and for the effects that it produces.

CHLOROGENIC ACID AND RELATED COMPOUNDS

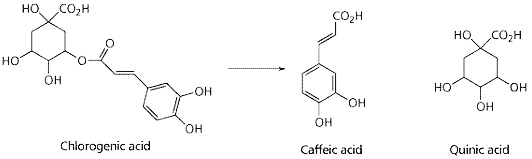

Chlorogenic acid and its ester, caffeic acid, are phenolic antioxidants found in Chinese herbs, and numerous herbs from around the world; they are especially prevalent in coffee. Chlorogenic acid makes up about 7.5% of a coffee bean; daily ingestion by coffee drinkers is about 0.5-1.0 grams. Chlorogenic acid is only partially absorbed from the intestines (about one-third of it), while caffeic acid is readily absorbed (about 95% of it). Some of the unabsorbed chlorogenic acid is metabolized in the intestinal tract by simple hydrolysis to yield caffeic acid, which is then absorbed (5, 6). In laboratory animal studies, it was shown that this component had antidepressive and anti-anxiety type actions (7). Chlorogenic acid and caffeic acids are components of vegetables, fruits, and common culinary herbs (e.g., basil, thyme, oregano), and are considered to be among the compounds that reduce risk of cardiovascular diseases and cancer.

Applied Food Sciences, a natural health products company, has developed an antioxidant from coffee that is 55% chlorogenic acid. The company is promoting a relatively new potential benefit: to regulate blood sugar (and, perhaps, help with management of obesity). Several studies related to the effect of this compound on blood sugar regulation are noted. In pharmacology studies, chlorogenic acid has been shown to reduce hepatic glycogenolysis (transformation of glycogen into glucose, by inhibition of glucose-6 phosphatase) and to reduce the absorption of glucose. Further, administration of chlorogenic acid lessens the hyperglycemic peak resulting from the breakdown of glycogen stimulated by the hormone glucagen. The studies also revealed a reduction in blood glucose levels (8, 9). In a clinical evaluation done in Moscow on 75 healthy volunteers, each of whom received either 90 mg of chlorogenic acid or a placebo prior to the test meal, results indicated the chlorogenic acid group had lowered the increase in blood glucose level by 15-20 percent (10). In a cohort study that evaluated coffee consumption and the risk of type-2 diabetes mellitus in a relatively large Dutch population, higher coffee consumption was associated with a lower risk of type-2 diabetes, even after adjustments were made for potential cofounders. Furthermore, the risk of type-2 diabetes decreased with higher coffee consumption (11). It is expected that chlorogenic acid is the main active component for this effect of coffee, as indicated by the above-mentioned pharmacology studies. However, coffee contains other blood sugar regulating substances, such as trigonelline. Coffee is much more than just a convenient and tasty source of caffeine; its other constituents are worthy of study and consideration for the overall impact from consuming the beverage.

APPENDIX: The Chinese Coffee Story

The Chinese do not consume coffee because of its potential health value either in terms of modern medical data or traditional Chinese medical concepts. Rather, it has been consumed until now as part of the fascination with Western culture that has grown during the past few decades, particularly after the anti-Western campaigns of the Maoist regime. Many Chinese look to the West for ideas about democracy, for modern music, and for coffee culture. This is a revival of something that had started prior to the revolution in 1949. In a 1998 submission, reporter Qiao Yi mentioned that (12):

Many decades ago, coffee culture in Shanghai was much more sophisticated than instant coffee. In the 1930s, when Shanghai was dubbed as a “paradise for adventurers,” Western restaurants and cafes mushroomed in the town that nurtured the city’s first generation of coffee lovers. Gu Juan in his 70s still cherished the memory of idling away his Sunday afternoon half a century ago with his friends at Red House or Shanghai Cafe on Nanjiang Road, which were demolished several years ago in urban renovations. “Most cafes were owned by Western people,” he recalled. Now, there are some 2,000 coffee shops in Shanghai and the number is growing quickly. A large variety of coffee is available in town thanks to these cafes, many of which were run with overseas investment and supplied with freshly roasted coffee beans from Western companies.

The Western companies, and some Chinese ones, too, are now supplying coffee beans grown in China. One of the best renditions of how coffee culture and cultivation has developed in China was relayed by Simon Hand in 1999, with the title The Coffee Story (or The China Coffee Story). Here is the relevant portion of his report:

China may be the land where tea began, but it’s a different story when it comes to coffee. The history of coffee planting in China only dates back a little over a hundred years, when a French priest successfully raised coffee plants in a valley in Yunnan province. Tea being the country’s preferred drink, however, coffee growing languished for 60 years until, in the mid-1960s, in a fervor of activity, the Chinese government cultivated 4,000 hectare of Arabica crops. Alas, the initial high hopes for the coffee crops dwindled almost as fast as they had been raised [the quality did not meet international standards], and by the mid-seventies less than 7% of that land set aside for this purpose was still being used for coffee plantation.

It was more than 10 years before China was to make another attempt at mass production of coffee. In 1988, a project began in Yunnan province between the Chinese government and the United Nations Development Program to develop the province’s coffee growing area. With the help of one of the world’s biggest coffee companies-Nestle-the planted area in Yunnan once again reached 4,000 hectares in 1995, and more than doubled by the end of 1998.

One of the main reasons for this, almost overnight, swing in popularity comes as part and parcel of China’s moves to reform its economic system in the eighties and to open its door to the outside world. The economic reforms have been hugely successful, with the average city worker’s pay packet almost fourteen times fatter than it was twenty years ago-and exposure to western influence has given the Chinese people a new feeling towards their disposable income. With education levels also soaring dramatically in the last ten years-fifteen percent of the population gaining higher education qualifications-the country is fast developing its own chattering class of new-wave intellectuals. And what better way to enjoy an in-depth discussion on the future of the Chinese political system than over a steaming cup of your favorite Java.

Although the days of Starbucks on every Shanghai street corner are still some way away [there are about 100 Starbucks stores in all China in 2003] the international coffee companies, Nestle and Maxwell House, have been quick to catch the trend and were among the vanguard of Western companies to enter the newly opening market. Their heavy investment in marketing and production in the late eighties and early nineties saw an almost instant return. Five years ago, says Dong Zhihua of the Yunnan Coffee Processing Plant, Nescafe [imported instant coffee] was the word for coffee in China.

From working with only ten plantations in 1996, the Yunnan Coffee Industrial Corporation (YCIC) is now the sole purchaser of the output of over 100 plantations throughout Yunnan province-40 in the Simao region-China’s premier growing region. YCIC is working with every one of these to make improvements to bean quality-installing quality control measures and supporting the growers with both finance and new technology. Yunnan University’s Agricultural Department has also been working with growers to try to rid the country’s crops of the coffee virus, Dry Leaf, having significant success by cross-breeding local plants with disease-free imported varieties.

Yunnan’s temperate climate, height above sea level and general geographical situation make the growing conditions comparable with both Indonesia and Colombia. Indeed, there seems to be no reason whatsoever for Yunnan not to produce some very fine, high quality coffee, especially now that the government is throwing its weight behind the venture.

Plans are already on the drawing board to build two new roasting plants in the province-one in Kunming and another in Simao. A sign of China’s optimism in the future of its coffee industry is the YCIC’s model factory above Kunming. With a capacity of 1,000 metric tons per shift, it is far beyond the corporation’s present needs-but Mr. Dong has every reason to believe that it will, one day very soon, barely suffice.

Note: As an update, in 2001, the coffee production in China was estimated at 18,000 tons per year, though the demand was pegged at about 30,000 tons. A hectare of land produces just over 1 ton of coffee, on average, so the production figure corresponds to about 17,000 hectares.

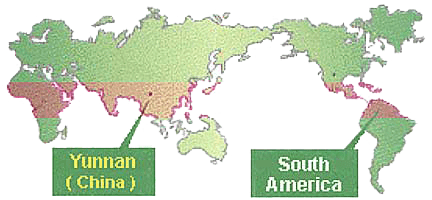

View of Yunnan coffee growing mountains, and their location relative to the world coffee growing area (map).

REFERENCES

- Nadkarni KM, Indian Materia Medica, (vol. 1, reprinted), 1976 Popular Prakashan Put. Ltd., Bombay.

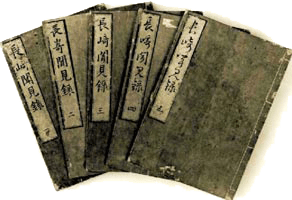

- Namba T, Masuse T, A historical study of coffee in Japanese and Asian countries: focusing on medicinal uses in Asian traditional medicines, Journal of Japanese History of Pharmacy 2002; 37(1): 65-75.

- Panagiotakos DB, et al., The J-shaped effect of coffee consumption on the risk of developing acute coronary syndromes, Journal of Nutrition 2003; 133(10): 3228-3232.

- Davids K, Coffee and health: health benefits of coffee, The Coffee Review 2001 (archived).

- Nardini M, et al., Absorption of phenolic acids in humans after coffee consumption, Journal of Agricultural Food Chemistry 2002; 50(20): 5735-5741.

- Gonthier MP, Chlorogenic acid bioavailability largely depends on its metabolism by the gut microflora in rats, Journal of Nutrition 2004; 133(6): 1853-1859.

- Takeda H, Caffeic acid produces antidepressive and/or anxiolytic-like effects through direct modulation of the alpha 1A-adrenoreceptor system in mice, Neuroreport 2003; 14(7): 1067-1070.

- Hemmerle H, et al., Chlorogenic acid and synthetic chlorogenic acid derivatives: novel inhibitors of hepatic glucose-6-phosphate translocase, Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 1997; 40(2): 137-145.

- Simon C, et al., Upregulation of hepatic glucose 6-phosphatase gene expression in rats treated with an inhibitor of glucose-6-phosphate translocase, Archives Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2000, 373 (2) 418-428.

- Abidoff MT, Effect of chlorogenic acid administration on post-prandial blood glucose levels, 1999 Moscow Center for Modern Medicine, Russian Ministry for National Defense Industries, Clinical Report.

- van Dam, RM and Feskens EJ, Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, Lancet 2002; 360(9344): 1477-1488.

- Qiao Yi, Putting more beans into China’s coffee culture, Shanghai Today, June 1998.

- Hand SJ, China Coffee Story, http://www.visit-mekong.com/stories/more/chinacoffee.htm, 1999.

September 2003